Protecting Your Joints:

By Idai Makaya

(This article originally appeared in Martial Arts Illustrated Magazine – March 2009).

All people are dependent on the health of their joints, not just to be able to train comfortably and properly – but also to maintain a decent quality of life.

One of the key focuses of my study of martial arts training and conditioning has been (and continues to be) the development of training methodologies which will not compromise the current (or future) health of the practitioner. Conditioning drills for martial arts are designed to serve a number of basic functions which mainly relate to the optimization of martial arts performance.

But by far the most important role of conditioning is to maintain the body in an optimal state of health and functionality, so that training can be carried out without the hindrance of compromised physical ability, debilitation, or injury. In summary; the basic function of a martial artist’s conditioning program is to allow progressive training – which will lead to progressive improvement – over a considerable proportion of the practitioner’s lifetime. This goal will be the central focus of this article.

One aspect of conditioning which is often overlooked – through ignorance rather than by design – is that of long-term health. There are many ways for a martial artist to successfully condition his/her body (and/or mind) so that physical abilities measurably improve. However, the only genuinely viable options are the ones which will not compromise the practitioner’s quality of life – both in the present as well as in the distant future. All training must be sustainable.

I personally will not endorse any particular methodology for general use among athletes unless there is a strong body of experience and evidence to suggest the method is safe over the athlete’s entire life. Some exercises are very effective in producing a performance improvement but they may be unsustainable over a number of years. My instinct is to advise athletes to avoid those drills from the outset and to focus on alternatives which are sustainable and will not cause problems in later life.

Much of what martial artists do has not been properly/scientifically researched, which is why experience and role-modeling are crucial when looking for evidence of physiological safety in conditioning and training exercises. I tend to rely on a combination of two sources of information when robust scientific studies are lacking about any particular aspect of training.

These are:

-

Carefully assessed long-term personal experience.

OR

-

The long-term experiences of credible role models for topics where my personal experiences are limited or insufficient.

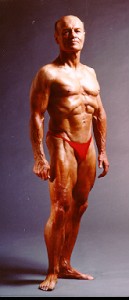

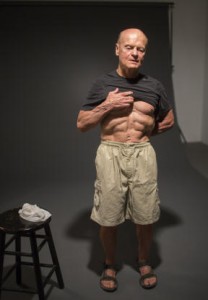

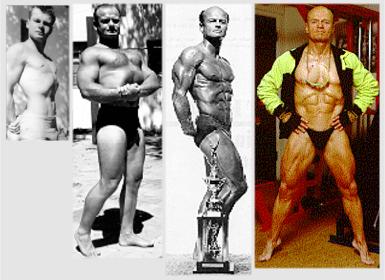

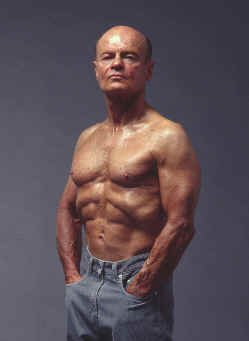

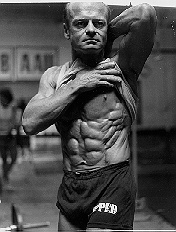

One such role model (who, incidentally, has shaped many of my own personal views on physical conditioning since my teenage years) is a well known bodybuilder named Clarence Bass. Clarence is one of the world’s most respected authorities on physical fitness and general conditioning and I particularly value his insights because they relate to sustainability and lifelong health and fitness.

Clarence was a columnist for Muscle & Fitness magazine for 16 years and has authored nine best-selling books on health and fitness. He was an Olympic weightlifter during his early years of training (collecting numerous city, state, regional and national American titles over a 20 year period) before focusing on bodybuilding. Clarence has also been a bodybuilding champion and won his category in the American Past-40 Bodybuilding Championships in 1978 and 1979. Of key significance is the fact that he was a bodybuilding champion in his 40s – and throughout his 50s and 60s was ranked highly in the age-group world rankings for Concept-2 Indoor Rowing. He is probably most famous for his ability to maintain a very low body fat for decades on end.

Clarence has the sort of experience we all can draw upon when it comes to pushing the body hard and remaining in machine-like shape. It doesn’t take a genius to realize that if he has been able to keep performing at the top level for so long he must know a thing or two about physiological preservation, motivation and discipline – qualities we will all do well to perfect in ourselves.

Clarence has also had his share of physical challenges, as one does when they have lived for 71 years, but he has been able to get past them and continue to stay in top shape.

I had the good fortune of getting Mr. Bass to answer some pertinent questions about physical training and protecting the health of athletes’ joints through good conditioning drills. His answers and explanations to my questions are included below:

Idai Makaya: One of the main goals of my training is to aim to be healthy and injury-free at all times – where possible – while still training at a high level. I’m also a staunch advocate of avoiding doing things for short or medium-term gain, which may then penalize the athlete in later life.

Clarence, do you think it is possible to push oneself hard – week in and week out – over many years – without eventually sustaining some form of permanent overuse injury?

Clarence Bass: No I don’t – and it’s not a good idea in any event. Training hard every

workout is not only flirting with injury, it’s a prescription for disappointment and disillusionment. The secret to long-term success is stress, and rest. Rest is as important as stress; both are required for continuing progress. I believe in the periodization model, which calls for training in cycles that ebb and flow. You push forward until reaching a sticking point, and then pull back and start up again – usually with a somewhat different emphasis. Done properly, each cycle takes you a little farther than the last. I believe that’s the secret to long-term training without injury.

(Idai Makaya: MAI readers may remember I wrote an article in MAI on periodization, early in 2007. That article expanded on the requirement in martial arts – and probably many other sports – for periodization to be applied in both short-term and long-term cycles. Conditioning approaches should vary with the age of the athlete and also with the length of training accumulated by the athlete.)

Idai Makaya: Alongside correct technique, nutrition and rest, one of the best ways to ‘injury-proof’ your joints is through basic strength training. So I posed the following question to Clarence:

Are there any specific strength exercises which you believe might be unsustainable over the long term? If so, which ones?

Clarence Bass: Some strength exercises are better than others, but I don’t recommend doing any exercise day in and day out. Change is a requisite for long term success. Both the mind and the body tire of doing the same thing over and over. Variety is the spice of life.

You must keep giving the body new reasons to adapt and grow. An exercise or manner of performance should be changed when the body stops responding.

(IM: that is, when you find you are no longer improving or progressing – this concept would also apply to many aspects of your technical martial arts training).

Clarence Bass: As a general rule it’s wise to change or avoid exercises that hurt. Some exercises feel good initially, but eventually become uncomfortable or boring. If an exercise (IM: or martial arts technique/drill) starts hurting, change it or stop doing it. Even the best of exercises get old after a while; it’s not a good idea to keep doing the same thing. Often a small change, in rep range, stance or grip for instance, will kick start a new cycle of gains.

Idai Makaya: The same rule applies (in principle) to methods of practicing martial arts techniques. As a beginner, new to training, it helps to do high numbers of repetitions of an exercise or martial arts technique – in order to ‘hard wire’ the brain and nervous system to perform techniques automatically. Once you become proficient, quality becomes considerably more important than quantity – so perform low numbers of high quality repetitions when you are more experienced. Train less frequently than a beginner would once you are very experienced because your intensity is higher and nerve pathways are ingrained. Once/twice-weekly repetition of all exercises and techniques is adequate to continue to improve once you are more skilled (such as Black belt level).

Idai Makaya: Clarence, do you do standard squats regularly (or any squatting movements to strengthen the legs) and are there any exercises which you have always done from your

youth – which you still do now – without any difficulty?

Clarence Bass: The squat comes about as close as any to being an indispensable exercise; it works the large muscles of the lower back, hips and thighs – and stimulates growth all over the body. I started doing barbell squats when I was 13 or 14 and have continued doing squats in one form or another during my long training career (IM: He turned 71 late in 2008).

I did regular barbell squats until immediately before my hip replacement in 2006 (without pain), and I am now doing the hip-belt squat.

Interestingly, it was not hip replacement per se that caused me to stop doing barbell squats. Hip replacement does not necessarily preclude doing squats. (My friend Rickey Dale Crain, the famous power lifter, recently squatted with 555 pounds within a year or two after having his hip replaced.)

(IM: The legendary high-kicker and kickboxing expert Bill “Superfoot” Wallace has also had a hip replacement some years ago but still performs at a high level even now, in his 60s. That’s good news for athletes – most joint injuries and arthritic conditions can now be addressed to a high level).

Clarence Bass: An unfortunate occurrence during the healing process (IM: Post hip surgery) forced my switch to the hip squat (explained further below). I traumatized my lumbar spine bending awkwardly to avoid pulling on my sore hip (shortly after surgery). As a consequence, compression of my lower back now causes numbness in my feet. The hip-belt squat allows me to squat without compressing the disks in my lower back.

(Clarence uses a hip belt which suspends a barbell from his waist so he can perform the squatting exercise without putting any pressure on the spine. This way he only works his lower body and the muscles anchored to the pelvis, without affecting the spine in any way).

Idai Makaya: Do you believe your hip injury resulted from something in your training (i.e. D’you think you would’ve got it anyway if it wasn’t for your training)? I have a lot of experience around joint-replacement surgery through my career in healthcare and it is not uncommon for sedentary people over 50 to have joint replacements – but many surgeons tell me they think joint-replacement surgery is becoming more common because more people are taking up sports and exercise. I am not of that view personally, although I have not seen any meaningful statistics on the topic to support either view.

I think the problem with many amateur sportspeople (including martial artists, I must say) is that they don’t condition themselves properly (if at all), which is why they are regularly injured and eventually end up chronically injured – but that’s just my personal opinion based on personal experience and general exercise science, only.

Clarence Bass: No, I think it had more to do with a congenital curvature in my lower back, which put an uneven stress on my hip. The wonder is that I was able to lift (weights) for over 55 years before my hip gave out. My hip might have gone bad earlier without training. No one can say for sure, of course.

(IM: You’ll find more details about this and other aspects of Clarence’s hip replacement on his website.)

It’s true that active people are having more knee and hip replacements. But I question whether activity generally is the problem. In my opinion, pounding the joints doing the same thing for years on end is the more likely culprit. Years of jogging, tennis or basketball are possible examples. Interestingly, a recent study found basketball to be the most injurious of all sports; weight training and aerobics were near the bottom of the list.

(IM: For martial artists this gives a strong case for cross-training and regularly adapting your normal routine to maintain your general ability levels and prevent excessive wear and tear of a specific type).

A more varied routine, including strength training, is likely to help preserve joints. (See below):

Idai Makaya: After your hip replacement has your training been changed or curtailed in any way (I know you said you’d dropped certain lifting movements, but that sort of evolution in

exercise selection is not unusual)? Do you think you train less hard now – or with the same intensity as before your surgery?

Clarence Bass: (I just explained one change). I’m training just about as hard as ever, but less often. For example, I do intervals on the Concept 2 rower, but only every two weeks. I do intervals on the Lifecycle on alternate weeks. I also do a hard foothill hike every week. Lastly, I train my body with weights one and a half times a week (one full-body conditioning session and one upper body-only session). I would characterize my current training as short, hard, varied, and infrequent.

(IM: If you’d like more detail Clarence has explained more of his post-surgery training adaptations in his new book, Great Expectations. The key thing here is for you to be aware

that health problems and past surgery need not be the end of your training career, but do consult your physician before attempting any physical conditioning after surgery or serious injury).

Idai Makaya: Are there any strength conditioning exercises you feel older and younger people should avoid to prolong their training careers?

Clarence Bass: I believe it’s wise to avoid jerky movements and exercises that pound or jam the joints. It also helps to change exercises frequently and spread the stress around your body. Again, avoid exercises that hurt.

(IM: The same advice applies to your technical conditioning in martial arts. Do all speed work against a target – such as pads, or a punching bag. Do not practice full speed kicks  and punches into open air. Practice jumping movements (kicks/punches) and jumping rope (skipping) on cushioned surfaces whenever possible and don’t do lots of high-impact jumping techniques every week without taking any breaks).

and punches into open air. Practice jumping movements (kicks/punches) and jumping rope (skipping) on cushioned surfaces whenever possible and don’t do lots of high-impact jumping techniques every week without taking any breaks).

Idai Makaya: Are joint problems inevitable as we age, in your view, or do you think it’s quite possible to have good joints throughout life?

Clarence Bass: Some wear and tear is probably inevitable. Much of it, however, can probably be delayed or perhaps avoided by doing the things we’ve been discussing.

Idai Makaya: Do you think good strength conditioning helps prevent the onset of degenerative conditions such as arthritis?

Clarence Bass: Yes. Done properly, resistance training protects and cushions the joints. Muscles work like shock absorbers for joints, cushioning blows that might otherwise cause damage. Strength training though a full range of motion (short of pain) also keeps joints flexible.

(IM: Many of you will be aware from my past articles that I strongly advocate the method of strength training Clarence has just described in order to prevent injury and also to enable you to perform advanced flexibility exercises – such as splits – with ease).

Idai Makaya: Do you think it is possible to always cycle through the same repertoire of strength exercises and general training routines – throughout your life – without eventually having to change them permanently? What I’m getting at here is whether sticking to the

same basic exercises/drills for decades will eventually cause the body to wear out in a specific way and thus prevent you from ever using those drills again in your life (as a result of injury and wear and tear).

In the last 3 years I’ve trained cyclically with weights – only using them for a maximum of 6 months a year (3 months on then 3 months off – during which I do body-weight exercises and/or isometrics only). I do this mainly to maintain variety and keep things interesting (My

physique, body measurements and capabilities haven’t really changed in that time – possibly because I don’t go all-out with the weights anyway). I guess I’m a martial artist, not a power lifter – and I think strength training beyond certain limits has diminishing returns for anybody other than a pure power lifter.

Clarence Bass: No. I think you’re wise not to overdo weight training while concentrating on martial arts. Less training is often better than more. It’s a mistake to add new exercises to an already full training program. Better to think in terms of substitution; cut back somewhere before adding to the program. One approach is to focus on weight training in the off season, as you seem to be doing. You might consider doing an abbreviated weight program when focusing on martial arts.

(IM: Once again, using a periodization approach to peaking at specified times of the year will help you plan how to condition yourself seasonally).

Idai Makaya: I’m glad you say that Clarence – that’s generally what I do. For competitive martial artists out there it’s wise to follow the advice Clarence has given in his last answer. Off-season, in such cases, is the time when you are not competing – or are a few weeks away from your next contest. About 2 weeks away from a bout or tournament, scale down the strength training to more basic, lower-volume exercises. It’s okay not to do any strength training in the week leading to a contest. But resume after the competition. If you enter a period of regular competitions (weekly tournaments, for instance) then follow a lighter in-season strength conditioning routine until the off season.

If you are well conditioned you will not be tired out by even quite a high level of strength training. The key to keeping energy levels high during the competitive season is to keep workouts short – even if they are relatively intense. Periodization (as outlined by Clarence earlier) requires training to reach a peak. If you don’t observe in-season and off-season approaches to all your training you will plateau at a level somewhat below your full potential and you risk over-training (burnout).

Clarence Bass: Thank you for asking my opinion on these matters. I hope the readers of Martial Arts Illustrated find my comments helpful.

Idai Makaya: Thank you for your time, Clarence.

In future articles I will continue to consult with well respected authorities on various aspects of conditioning and fight-preparation, as well as looking at other training topics of interest to the martial arts fraternity. Happy training until then!

If you want to find out more about Clarence Bass and hot topics in fitness training and conditioning, visit his website www.cbass.com