Report by Idai Makaya

Alan McDonogh and myself attempted to complete an ‘Everesting’ Cycling Challenge on ElliptiGO bikes on 12 August 2017. The 14-minute video summary below outlines our full Everesting challenge and also covers my own preparation for the challenge. The information below the video explains our preparation and execution in deeper detail (mainly focusing on the psychological aspects of the challenge, which are harder to convey in a short video).

The idea of completing the ‘Everesting’ Challenge on an ElliptiGO bike has been floating around for some time (on social media chat-rooms and even among some of my close riding buddies) but it wasn’t until earlier this year that I first contemplated the possibility of doing it myself.

‘Everesting’ is actually pretty simple, as concepts go. You ‘just’ ride up and down a very steep hill – until you’ve climbed a cumulative height equivalent to that of Mt. Everest (8,848 m or 29,029 ft). It is that simplicity, along with the fact that I’m not a great climber (so the challenge would be incredibly difficult for me to complete!) that had first made me take it seriously. That simplicity – and also the loss of my brother Garai Makaya – who passed away on 11th February 2017.

Garai Makaya (16 November 1975 – 11 February 2017).

I had wanted to find a cycling challenge that would stretch me to breaking point, which I could face in Garai’s honour and dedicate to his memory. ‘Stepping’ (quite literally!) out of my comfort zone had seemed like the best way to do this, because I had wanted it to mean something. I had wanted it to be so tough that I’d never forget the achievement. So I’d connected with Hells500 who are the ‘custodians’ of the Everesting challenge and we’d made the plan official (after they’d confirmed that the challenge would be open to ‘stand-up bikers’, like ourselves).

A few months had passed with no further activity – as my personal life had been too ‘hectic’ to really allow me to focus on this plan – and I had needed to ease myself back into high level endurance training after my brother had passed away. I’d realised that riding with other people had really helped me with this return to form – and it had forced me to keep my training commitments. So training (and riding in Audax events) with other athletes is how I had built myself back up – so to speak – and I’m grateful to all the athletes who’ve assisted me in this way in 2017.

Tim Woodier attempting the Everesting challenge on 14 May 2017…

On the ‘Everesting front’ my teammate and buddy Tim Woodier was the first person to attempt an Everesting challenge on an ElliptiGO bike. He did so on 14 May 2017 – and was successful in his first attempt. It was an awesome performance and had shown that this ‘thing’ was really possible on an elliptical bike.

But Tim is one of the best hill climbers you’ll find (living in the Welsh mountains, as he does)! So some of us had started wondering about how slightly more ‘normal’ people might fare in an ElliptiGO Everesting challenge. And, initially, the evidence was not encouraging…

Two really strong American ElliptiGO riders had made an Everesting attempt in the USA and were unable to get to halfway (stopping short of 4,000m). Then my buddy Stuart – one of the most accomplished and talented long-distance ElliptiGO riders I know, had also made an attempt – and he had also withdrawn before full completion (with just under 6,000m climbed).

Strangely, rather than putting me off, those early forays into Everesting by fellow ElliptiGO riders (although mainly unsuccessful) had actually spurred me on – and had made the prospect of facing the Everesting challenge even more exciting for me! Those withdrawals by riders whom I respected had told me it would be a genuine test, rather than a foregone conclusion. And that was what I had been seeking.

I was now truly expecting to suffer during the Everesting attempt – and to be stretched to my breaking point. As an ultra-endurance athlete, that prospect of being stretched to my limit is actually a great one to contemplate! Only in the darkness can we really see the stars… It is only when operating at our true limits that we can begin to learn new things about ourselves – and I simply couldn’t wait to do so!

I was beginning to get back into proper training 6-8 weeks after Garai had passed away, with a weekly speed session (with my new training buddy Thomas). And I had also started a series of monthly Audax Group challenges from around that time, so that the combined speed training and occasional long-distance events had all brought me to an extremely high level of fitness (despite only riding about 100-miles per week, in my routine training).

Such was the intensity of my training with Thomas (from the beginning of April 2017) that I was regularly setting personal-best times on my local 20-30 mile speed training courses. And although there was no meaningful climbing in any of my routine training I’d still felt (by June 2017) that I was ready to take on something as tough as the Everesting challenge.

Speed Training with Thomas, in June 2017 (Photo by Alison Mead)

My belief was that higher-intensity training would get me into great endurance shape, despite a low overall training volume. I have always tended to train this way – and especially so after a few forays into high-volume endurance training over the years (which had generally left me feeling really strong – but also really slow).

So my feeling is that for non-competitive riding (where a comfortable and sustainable pace is required for success) lower-volume but higher-intensity training will suffice, because the lower effort level required for sustaining a very long ride feels almost ‘easy’ when the overall training pace has been so much higher and more intense than the planned event pace.

I believed Everesting would turn out to be mainly a mental battle – and that was pretty much what had happened. My buddy Alan and I had decided, at quite short notice, to team up and make an attempt at Everesting together (having had lots of experience of riding together in really long and really tough ElliptiGO endurance challenges, over the years).

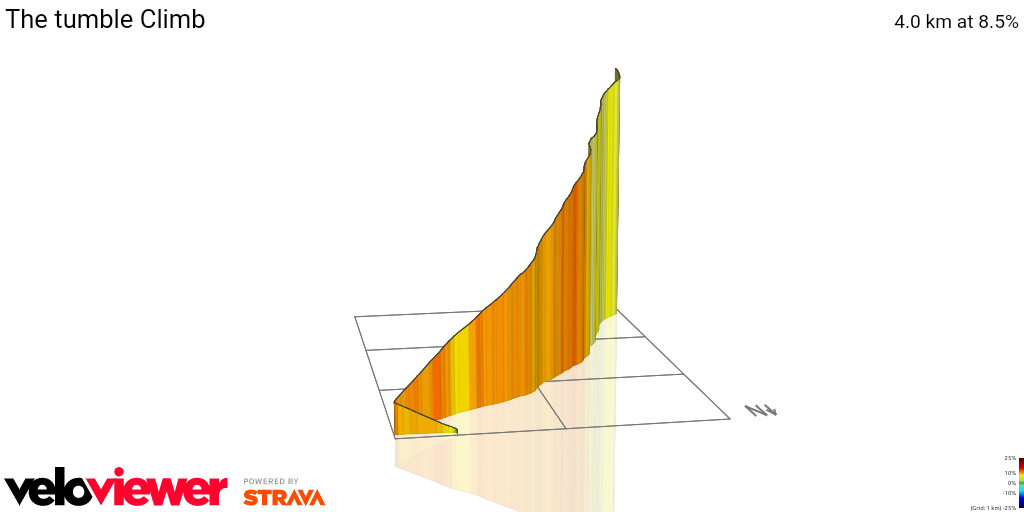

With Tim’s help we chose a climb called ‘The Tumble’ for our Everesting attempt. The Tumble is situated close to where Tim lives, it is about 5km long and has just under 400m in total ascent (meaning 23 repeats would be required to exceed the height of Mt Everest). The hill profile for The Tumble can be seen on the 3D diagram below:

The video link at the top of this report (which is also displayed below this paragraph) pretty much outlines our Everesting attempt (audio-visually) and hopefully makes it all the more real. But the paragraphs below go into a bit more detail about the challenge, in relation to the psychology applied (and in relation to my immediate feedback after I’d finished). If you first want to find out how it all unfolded you can watch the video and then read the feedback, afterwards…

My Immediate Post-Ride Feedback:

On the day after Alan and I had completed the Everesting attempt my buddy Stuart had asked me if I’d considered quitting at any point in the challenge. And he also wanted to know more about what had worked well for me and what hadn’t. So I sent him the message below, with my views:

My main focus for success was related to dealing with the tricks the mind plays on you when you’re under pressure (and I’ll now explain how we avoided letting those ‘tricks of the mind’ sink us in this Everesting challenge)…

Getting GOing on 11 August 2017. (Photo by Kim McDonogh)

Truthfully speaking, quitting was never even a remote option for me, GOing into this. I had made it impossible for myself to withdraw by my own choice (by simply telling everyone about it, by linking the challenge to my brother, by live posting on social media, etc) and I never came close to actually quitting at any point in the ride.

That doesn’t mean it wasn’t all hanging in the balance at times – because it was – and that’s because I was really afraid my body would let me down (through the sheer physical strain I was experiencing). The spirit was willing but the flesh was weak, so to speak…

This ‘quitting and mind games’ part of the challenge is probably the most important to consider for anyone who takes on something like this Everesting challenge. Your brain starts the ‘trickery’ almost from the first hill rep. So every hill rep had a new challenge for us (challenges such as muscle cramping, or some ‘weird thing’ going wrong – all the time, throughout most of the ride).

The Tumble stood menacingly on the horizon as we reached Abergavenny…

And that sort of worrying makes you uncomfortable in itself, because you think you are not in control. So I was always afraid that something catastrophic was about to happen to my body – like a muscle pulling, or a hand cramping beyond recovery, etc.

Speaking of which, I really need to look into my ‘cramping issues’. I seem to get muscle cramping from time to time, but very much in yearly cycles. I have always had a problem with cramps (during or after exercising). Even as a teenager, when playing tennis at school in the hot sun, I’d often start cramping later on in the evening (or while I was sleeping during the night) after particularly grueling tournaments on hot days.

I have noticed that it is very much related to exercising in the heat – whenever I first get the ‘cramping problem’. But after the first time I have experienced a bout of muscle cramping it seems to ‘set in’ longer term and my susceptibility to cramps just seems to stay with me for months at a time, regardless of what type of training I am doing. But this cramp susceptibility eventually goes away again after a few months – and it often stays away for years at a time…

So I had the cramping problem in late 2011-2012, but it had stopped by mid 2012. It then came back one hot day when I was training for PBP in 2015 – but only mildly that time around – and it stuck around for about 3 months, that time (which actually helped me, because I regulated my training intensity to avoid further cramping). Then, last month, when I rode the ElliptiGO Arc bike for the first time after a 6-week break (I’d been waiting 6-weeks for it to be serviced) the cramping came back in a big way. And it has been with me since then.

Leaving it all on the road after training… the first time I was hit by cramps in 2017 – after riding the ElliptiGO Arc 24 bike in a tough training session with Thomas.

And cramping was certainly a massive problem in this Everesting ride, from pretty early on. My feet were ‘trying’ to cramp underneath their soles. My right hand was ‘trying’ to cramp in the palm and fingers – and mainly on the descents (whenever I’d braked). And my biceps muscle on the left arm actually cramped fully (but that bout of cramps in my biceps just lasted for one rep of The Tumble, thankfully).

Alan completely cramped up on the inner thighs (which is usually the most common place for cramps to hit you when you are ‘overdoing it’ on the long-stride ElliptiGO bike). I did start using high dose electrolytes later on in the ride – and I thought I saw an instant change in the cramping situation when I did so. But that was also evening time (and I have noticed that I only seem to cramp up when riding during the heat of the day, but as soon as things cool down again I don’t tend to cramp up any more).

The reduced cramping susceptibility in cooler weather is very much like the fact that I never have cyclist’s ‘hot-foot’ (foot discomfort during long rides) at night, or when temperatures are low. I only experience foot discomfort during rides when the sun is directly shining on me (and ambient temperatures are high). I think it’s because my feet swell up in hot weather and the shoes get tighter – causing the foot discomfort. I’ve learned this over the years (as you do, when constantly optimising your comfort for long rides).

On this Everesting ride my feet were actually very comfortable because of the very slow cadence and also because temperatures were never particularly high.

But that is why I bring up the ‘mental trickery’ aspects of this ride. My brain was constantly trying to trick me into giving up, by making me think things were going wrong in major ways, when they weren’t. And every time I closed off one ‘line of inquiry’ my brain IMMEDIATELY tried something else to try and trick me into giving up!

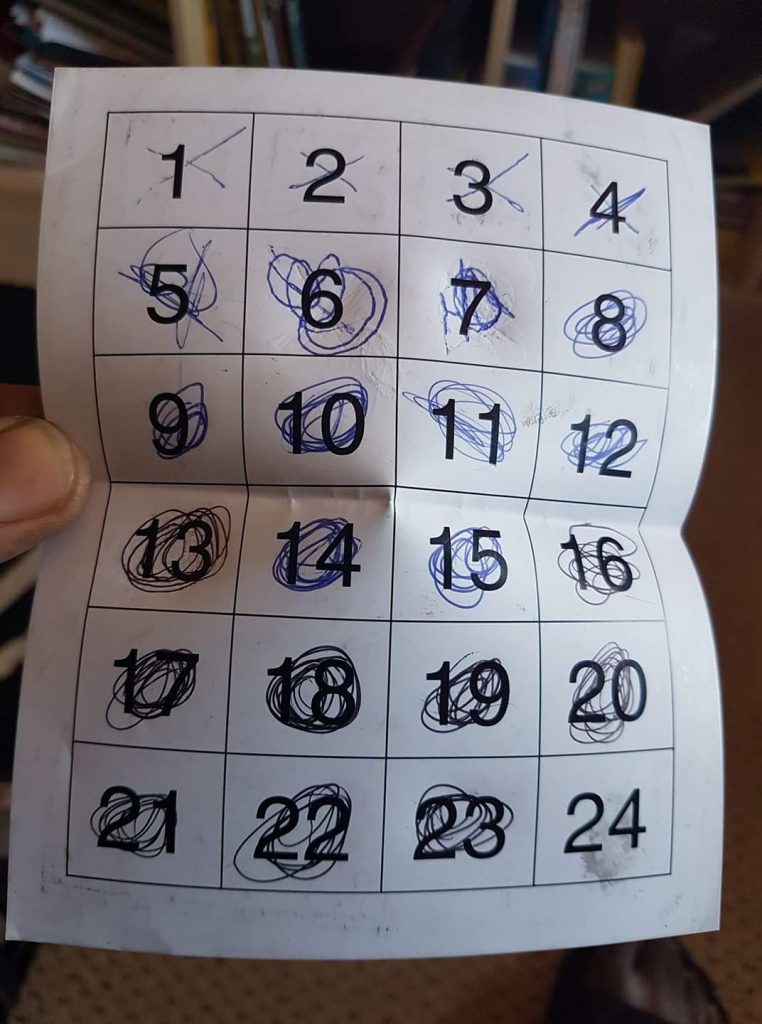

Speaking of quitting, Alan did actually try to withdraw from the Everesting attempt – around rep 7 or 8 – but Tim had done a great job of just ‘sitting him out’ for an hour and allowing me to then catch up on his reps. Alan was a whole hill rep ahead of me by then, because he was not stopping (or eating) – he was just GOing up and then immediately GOing back down the hill, without taking any breaks. I, on the other hand, had stopped at top and at the bottom of every hill rep I did (to eat, to post my progress on social media, to record my reps, etc). But, after I caught up to him Alan and I had continued together (from rep 8 until the very end of the challenge).

As mentioned earlier, during the period before we’d joined forces Alan had also been struck very hard by cramps – and that sort of thing knocks your confidence, big-time… Also, after just 2 or 3 reps, we were already down to using gear 1 (our lowest gear!) for almost the entire climb... So the ‘trickery’ of the mind had then started asking us very pertinent questions, such as:

“How on earth can you even finish – if you have no spare gears, so early on? And you have barely done 10% of the ride. And you are cramping badly. If you have no lower gears left then you will have to push harder and harder – because there is no option to reduce pedaling resistance. So how will you do that (when the cramps actually get worse if you push harder)?”

That particular argument (about our gearing) was weighing heavily on us both, from quite early into the ride. How would we continue for 20 more reps if we were already struggling to scale the mountain after just 3 reps? It was a great question!

At the bottom of the mountain, starting hill rep 9, Alan had actually tried to suggest that it wasn’t worth the battering of continuing until failure – just to get an ‘honourable exit’ (the brain trying its games again?) because, in his view, if you obviously can’t make it to 29,000 feet then what benefit is there to doing ‘only’ 15 hill reps (rather than just 9 or 10 hill reps)?

He’d asked me: “Why should I continue, if I know I wont finish?”

But did he really know this for a fact, I had wondered?

At that point I’d promised Alan that it was just about his pace (and him fasting for 12 hours up to that point) and I had suggested that if he just stuffed himself with food (and rode behind me, to keep a slower pace) he would likely recover over the next 3 or 4 hrs. And that is exactly what happened. He became more and more ‘normal’ with every hill rep after that. So we decided to just ride in formation (because every time Alan went in front of me he just got faster and faster – without realizing – and that was problematic for him).

Feeling the strain (and drowsiness) in the early morning hours…

I had borrowed Tim’s handlebar-mounted music system (I don’t do headphones on bikes) in order to counter the boredom I had expected to encounter in the challenge but I didn’t need it much because I had someone to ride with all the way through the night, which I hadn’t expected. Alan also had music and we’d both started playing our music in the wee hours of the morning, when we didn’t feel like chatting any more (his music used earphones, so my ‘sound system’ would not disturb him).

For me, the music had made it feel like the ride was just beginning again. I became totally refreshed – and upbeat – when the music had started playing (after initially having felt like nodding off, from about 3am). In fact, I almost ‘killed’ Alan on the first rep I did with music playing – because I didn’t realise just how fast I was riding (and he had to push hard just to hang onto the pace I was setting)!

But once Alan had got past that ‘really bad phase’ in the afternoon our success simply became about staying safe. We both knew we were going to pull it off and we just had to ‘wait’ until it was finally over. We had a great routine at the top and bottom of the mountain – and I was having meals at the top and then again at the bottom of the mountain, throughout the day – which is why energy flow was never an issue for me in the ride. I basically over-ate.

In the night time we had switched our ‘camp’ to the base of the hill (where my car was parked) because it had got so cold at the top of the hill by then, so we had wanted to minimise the time spent up there and had switched our admin tasks and eating to when we got back to the base, instead of at the top). So we were only eating once per hill rep, from that point (at the bottom of the hill – where we filled out the checklist, filled up on water, and I posted my photos to Facebook, etc).

Alan and I had both remarked about how this was no different to any other tough long ride we’d done (except for the higher level of support – and having all our kit in one place whenever we had stopped). It was a lot like having a support vehicle on a tough long ride, except that nobody needed to drive the car to support us!

But Tim was actively supporting us, locating himself at just past half way up the climb – or moving up and down the hill to take photos – or bringing down the stove and plates for our meals. Tim even cooked us a ‘proper’ meal, on Alan’s gas stove, before finally leaving for the night…

There was no real boredom during the Everesting challenge (not more than you’d expect on any 24-hour ride). The descent was so technical that your full concentration was required just to negotiate it safely. And the climb was so intense that you needed to really focus on everything you were doing – whilst also looking out for the specific landmarks to tell you where the most difficult (or the easiest) parts of the climb had commenced.

It was tough, but in a very manageable and predictable way. And it was mainly tough in the heat of the day – and nearer the beginning of the ride, when it was still easier to pull out (and when we were still worried about all sorts of stuff going wrong). But once we had all accepted that we were in it for the long haul (and by ‘we’ I mean us and our subconscious brains which had desperately tried to sabotage the effort!) then it was pretty methodical.

Our check-sheet was finally filled out… 23 hill reps completed in 25hrs & 18min!

The last 2 hill reps were slightly more difficult for me, because of impatience. You know you are done, you know there is nothing that can stop you – except God himself – and yet you also know that you still have another 2hrs of riding ahead of you. The slowness is difficult to come to terms with at times like that.

But we were also quite jovial in the last 3 reps – it was almost a celebration. You know you’ve succeeded at that point. So there was no celebration when we did actually succeed – because the celebration happened much earlier (when the ‘mind games’ were finally defeated and we knew we would definitely make it).

As for the descent, I was pretty scared of it for most of the first day. But as it got darker (and the traffic had eased off slightly) it got easier. Sadly, we had A-road traffic diverted onto the hill that day and – on average – I’d say we had a car passing us at least once every 5 seconds (at the peak of the day’s traffic).

But in the night I had actually started to enjoy the descent. I think it was just that I had finally learned every metre of the descent by then – and also because my right hand had finally stopped threatening to cramp whenever I had pulled on the brake lever (meaning that I was no longer scared of something terrible potentially taking place)!

And – speaking of the descents – it had got so cold by nightfall that we had to put on our jackets every time we reached the summit of The Tumble (or we’d have almost certainly succumbed to hypothermia during the 7-minute long descents). But the climbs back up the hill were still so intense that we then had to remove our jackets at the base of the climb (and head back up wearing only our t-shirts and reflective vests).

We also dimmed our headlights to save battery power on the very slow ascents (because the visibility was still good with low lighting at that slow pace). But during the fast descents we’d have to turn up the headlights to full power (to enable us to see potential hazards from a distance – while travelling at speeds in excess of 60km/hr)!

The final cumulative elevation reading was 9,027m of climbing…

Also, my fear of the brakes fading had reduced later in the ride, because my bike’s brakes had actually got stronger and stronger as the ride had progressed. It turns out there was probably old chain lubricant which had got onto the rims of the bike (I oil my chains every time I ride the bikes and sometimes excess oil drips off onto the rim when I do so).

The main ‘problem’ with this particular ElliptiGO 11R bike I was using for the Everesting attempt was that it’s hardly ever used (being my special-edition personalised bike) so the chain oil seems to really ‘bed-in’ if I spill any onto the rim. This bike has always had weaker brakes than my other one, especially the back ones, because of this oil issue. But with all the descending in the Everesting challenge the rims and pads had probably ‘worn down’ enough to have finally lost their grimy layer – and by the time darkness fell my brakes were perfect! So I was not so scared of the descents any more…

Job done! 23 reps of The Tumble (and over 9,000m of climbing) achieved!

Post-Ride Summary:

In terms of recovery, all the stress was likely to have been in the head, because (physically) I’d never have guessed I had ridden for a full 25hrs when I got up the next day (if my memory of the event had somehow been wiped away!). I felt no discomfort at all the next day (whether related to exercise stress or to pressured contact points). I was not even sleepy when I awoke the next day!

On the day we’d finished riding (13 August 2017) we’d slept for about 2hrs – in the afternoon – and then we had driven back home, that same evening. I had then slept for another 9hrs (overnight) and awoke at my normal time for a work-day, feeling perfect. It’s like I had just done a relaxed 200km ride on the previous day (not a 25 hour one)! Obviously, the descents don’t count at all when you’re doing hill repeats, so we really ‘just’ did a hard 113km of riding – and that’s what our bodies have probably experienced, physiologically…

I am now hoping this report inspires someone else to attempt to ride the height of Mt Everest. After all, we did it standing up! It’s doable!